When Marnie Was There: the Studio Ghibli movie explained

Help! When Marnie Was There is confusing me! What just happened? Why

did it happen? If X

is true, wouldn’t that contradict Y

? Is

Marnie a ghost or something else? Are they lesbians? Thinking about

this movie is like solving a Rubik’s cube; you solve one face only to mess up

another. And if you think way too long about the epistimological implications of

Marnie, at some point you wind up having an existential crisis and realise that

all of this is just fiction in the first place, and that’s not a fun conclusion.

No fear, I am here to get to the bottom of this. I have the (literal) ground reasearch to get to answer all your questions without, hopefully, running into contradictions. I deeped dived so hard.

Blurb

This movie is about Anna, an adopted girl who is sent to the country to live with an old couple in order to heal from her asthma. There she meets a girl, Marnie… seemingly…

What is Marnie about?

It is about resolving the experience of feeling undeserving of love; Anna

apathetically declares herself an outsider to an invisible magic circle

that separates her from people who are deserving of love and acceptance and are

entitled to have friends and fit into social functions, unlike herself. She

refuses to accept love of her foster mother, Yoriko, and is cautious about the

friendliness of people. Anna, the girl who shut her heart,

as Japanese

promotional material for the movie put it.

At the root of all of this, she doesn’t love herself. No one can begin to love others if they can’t love themselves.

Her inability to give and receive love is stunting her growth as a person. So

this story is consequentially a tangle of many other things. It is about

feeling lonely. It is about being unsure if you have any friends. It is about

being too aware that people don’t care about you. It is about being unable to

reveal a vulnerable side to yourself because you know it will be dismissed or

trivialised (pic at the topic of this article is related). It is about having a

friend

who in turn have other friends who are more fashionable and

successful than you, and being unsure you’re a good enough friend, and supposing

they’ve upgraded their social circle to exclude you, and then you wonder whether

you can call them a friend, or anyone ever. So Anna meets Marnie, where all of

this is worked out under mysterious circumstances.

This movie is not for everyone

A lot of people will not understand this movie because they not know what it is

like to live like this, and these are things they’ve never experienced. They

will comment that Anna is a deeply unlikable character and that the story is

boring. I am not offended when people say Marnie is a middling or bad

film, because I just comfortably know that they didn’t get it. This sounds

arrogant, but I don’t know any other way to put it. Among people who know what

Anna represents, it’s like a secret gem of a movie. It fits the very definition

of cult appeal. This story’s barrier of entry isn’t something low and wide,

like finding love

or whatever. No, its barrier of entry is decidedly

narrow—and in compensation, its barrier of exit is high and emotionally

purifying.

The story of this movie was adapted from the short 1967 novel of the same name, by Joan G. Robinson. The novel is a deeply personal work and clearly wasn’t written for the mere sake of publishing a book, but because the author needed to say something. I have read this novel perhaps deeper than the movie, so I will make small references to it but not rely on the assumption you’ve read it.

Plot

Let’s establish the structure of this film into basic plot points to make things digestible.

-

Marnie lives and dies.

Marnie begat Emily, Emily begat Anna. Emily dies, Marnie takes care of Anna. Marnie dies, Anna becomes a foster child.

-

Anna has a panic attack.

Anna has a panic attack when her attempt to show her artwork is immediately dismissed.

-

Anna is sent away from Sapporo

She stays with the Oiwas, finds quiet company with Toichi, and discovers the Marsh House.

-

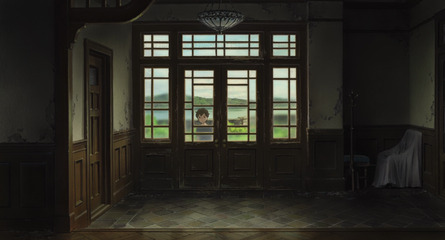

Anna dreams seeing a girl in the Marsh House

Anna has a dream where she seems a girl through one of the Marsh House windows.

-

Anna meets Nobuko

Anna meets local girl, Nobuko, at the Tanabata festival. She emotionally wrecks Anna.

-

Anna meets the girl from her dream

Anna meets the girl she saw in her dream.

-

Marnie teaches Anna to row

Anna learns the girl is called Marnie, she lovingly gives Anna rowing lessons.

-

Marnie momentarily disappears

Marnie briefly disappears when Anna tries to recall the Oiwas.

-

The house party

Anna gains insight into Marnie’s home life. They dance under the moonlight.

-

Reconciling Marnie’s reality

The next morning, Anna visits the Marsh House at low tide to find it’s abandoned again.

-

Anna looks for Marnie again, encounters Hisako and Sayaka

Anna meets old lady painter Hisako, and then Sayaka, a girl moving into the Marsh House who found Marnie’s diary.

-

Anna dreamily meets Marnie again

Anna and Marnie go mushrooming together. Anna reveals she’s an orphan, Marnie reveals she’s abused by her maids.

-

Anna and Marnie head to the silo, briefly interrupted by Sayaka

Marnie disappears while they walk to the silo, being interrupted by Sayaka. Marnie then disappears for good.

-

Anna reaches closure

Anna dreams Marnie begging she forgives that she left her. Anna forgives.

-

Anna finds out Marnie was her grandmother

The diary Sayaka found, written by Marnie decades earlier, aligns with what Anna experienced. Anna makes the connection when Anna is shown a postcard with the Marsh House.

Detailed plot summary

Just so we’re all on the same page, let’s first discuss what actually happens in the movie at all the major plot points.

- Explaining Marnie and Anna’s background

-

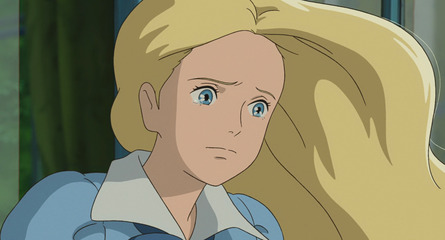

Marnie is born to wealthy parents who are egotistic and do not know how to be a mother and father. They are more concerned with being fashionable than establishing an emotional connection with their child. This absence of any actual parental figure makes Marnie functionally an orphan. Marnie copes by fixating on her material fortunes and insisting she’s

the luckiest girl in the world,

as if to convince herself. She has to survive the abuse of her maids, and has no one to tell.

Marnie would convince herself and other her parents were amazin.

Her parents were more concerned with their fashionable lifestyle and not Marnie.

Marnie is being neglected. Marnie grows up determined to raise her own child with love, Emily, but her attempt misses the mark when she sends her to boarding school. Emily grows up to have Anna. Emily, just like Marnie’s parents, recklessly neglects her insofar as dying in a car crash while on holiday away from baby Anna. Baby Anna briefly comes into care of Marnie before she dies. Anna is then adopted, who now has attachment disorder. While Anna’s early childhood was apparently sometimes happy, according to some framed photos, she can’t totally and reflexively accept the love of her foster mother. Things come tumbling down when she discovers they’re secretly paid a subsidy to care for her. Her foster mother, Yoriko, remarks that her

ordinary face

is a recent phenomenon at the beginning of the movie.

Things seemed to be going well for Anna. - Explaining the opening scene

-

In many ways, the opening scene is a hard shibboleth between those who will

get

the rest this movie and those who won’t. It’s not an exposition of characters we’ll see again, it’s more like a dip of the toe before entirely plunging in.A teacher walks over and asks Anna to see what she’s drawing. She’s shy at first, but eventually decides that showing her artwork may be recognised as an exceptional gesture from her—that showing something so personal might payoff with praise and sincere fascination. As she’s just about to hand over her sketchbook, the teacher is casually distracted by something else in the playground, and walks off; it was only feigned interest. Her attempt at putting herself in a vulnerable position was met with no interest. Her gesture went unrecognised. She has a panic attack.

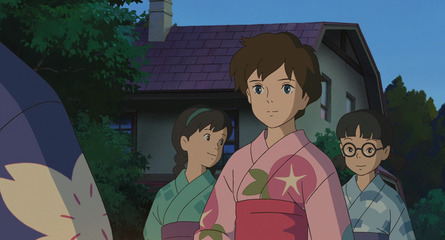

She’s excited to reveal something personal about herself.

but that’s immediately rejected soon after.

Thought she was going to throw up here. My emetophobia kicked in :/ Few words are exchanged here, yet what plays out is remarkably complicated. She isn’t just shyly offering a drawing, she’s pushing herself. The way the teacher’s so casually dismissive is deeply glib and condescending to her—and not just in a static sense. It’s like an advanced version of The Ick, where Anna suddenly realises the motive of the teacher was entirely different, and in a devastating cascade, so were the motives behind all events since first meeting. In a flash, the entire universe reconfigures before her eyes. She can’t take it anymore.

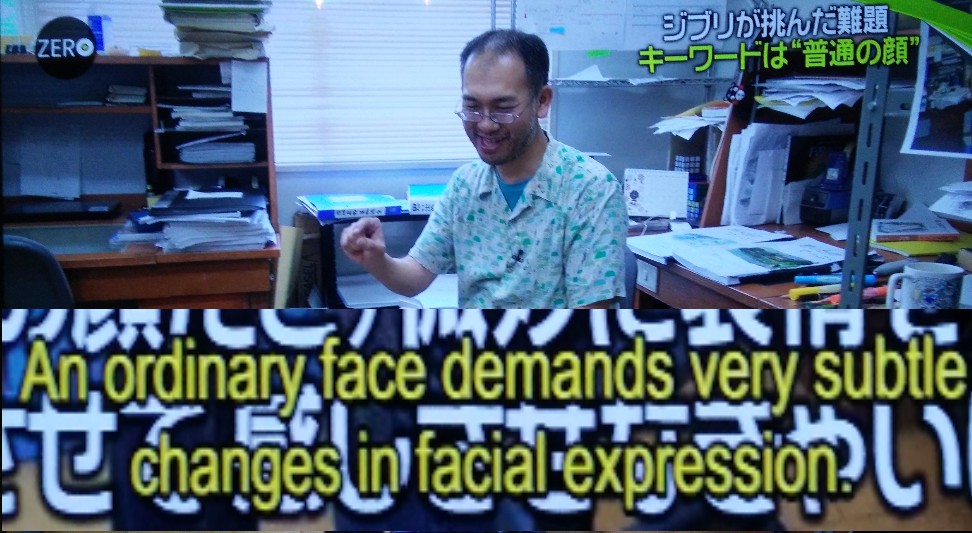

What’s also interesting is how so much of this is conveyed through facial expressions. Yonebayashi said in the blu ray extra that he made a special committment to the facial expressions of the characters. Not comically wacky boneitis expressions, but carefully measured shifts in mood; the difference between facial expressions in Ghibli animation vs US animation is the difference between an eloquent speech and an autistic ramble. Anna’s self defence mechanism is to put on a

ordinary face

. The moment she realises she is put in a vulnerable position, such as when people begin to toy with her feelings, she puts on her face to shutter everything immediately, like the sudden vertical descent of a fire curtain.

Said it himself. - Explaining high tide / low tide

-

So Anna is now away from Sapporo, with the Oiwas. At low tide she takes a cursory look around Marsh House. Seems abandoned enough. The tide comes in. While out in Toichi’s boat, she catches a glimpse the Marsh House windows lighting up. Alas, it was just the low sun… or was it the high tide? These scenes broadly familiarise us with Anna’s lucid mode; here we are just adjusted to how reality works in this movie.

Abandoned at low tide.

Tide comes in and the house kinda lights up.

What’s going on?

Must’ve been the low sunlight… In a dream she ventures across marsh, smoky and half tide, and sees a girl through the window of the Marsh House. She then wakes up. We’ve now been familiarised with the setting of Anna’s dream mode; this kind of setting appears again later in the movie.

Anna’s dream mode is visually distinct. She can’t go anywhere but stand on that grass. - Explaining Toichi

-

Just a small thing. Toichi’s name is wordplay on

eleven

in Japanese; he was the eleventh child among his siblings. Now, how can someone from such a large family be so lonely? This small detail is a comment on the nature of loneliness.

Poor Toichi - Explaining Tanabata

-

The appearance of Vega and Altair in the sky. Tanabata is a Japanese festival that celebrates the meeting of the two deities, Orohime and Hikoboshi as represented by the stars Vega and Altair respectively, who are otherwise separated in the sky by the vault of the milky way. This seems like a metaphor for something, eh.

But first, let’s just have a look at what goes on at the festival. Anna is introduced to Nobuko, and she’s reluctant to be friendly with her at first. When Nobuko asks her where she is from, Anna answers. She lets her guard down a little and smiles. However, Nobuko is immediately distracted and runs ahead to her other friends; it was only feigned interest. This is a repeat of the opening scene.

Anna smiles a little when Nobuko asks where she’s from.

Immediately puts on her ordinary face

when ignored.A little later, an explicitly vulnerable part of Anna is now blown open, her wish to

be normal everyday.

Not only is she unable to explain what that means, it’s immediately trivialised when Nobuko tactlessly moves onto commenting on Anna’s racial characteristics. This is the equivalent of punctuating a reply to a serious message with almao.

This again, breaks Anna. She calls Nobuko a fat pig, etc. - Explaining Anna and Marnie’s first encounter

-

So on the night of the Tanabata, after Anna runs off. Just as the gods Orihime and Hikoboshi are to meet, so are Anna and Marnie. So Anna flops herself beside the marsh at high tide. She collects herself and begins to walk away. Suddenly, a candle is shown to mysteriously light up. It’s as if to indicate how metaphysically strange things are about to be. This candle is probably a reference to the Japanese lyrics of one of the movie’s soundtracks,

Anna,

a small candlelight shining deep in my heart.

A candle in the boat suddenly appears. She rows across the marsh and meets Marnie. Anna is a little bit confused, especially Marnie’s stealth behaviour, but wins her trust after Marnie promise to keep each other a secret. Let me repeat that again, Anna wins Marnie’s trust only when Marnie says

you’re my precious secret

and asks her to keep her a secret in return. This is all is apparent in Anna’s facial expressions. What’s so good about this deal? It’s the fact that Marnie in some manner, even if it doesn’t make much sense, is treating Anna uniquely in a way that somehow feels good. Remember that Anna still views herself as outside of the invisible magic circle, she wouldn’t even bother getting to know Marnie if was under the usual conditions of making friends with someone with the expectation of further inveigling oneself into their social circle. This makes Anna smile.

Anna isn’t sure about Marnie at first.

But straight after Marnie’s proposal to keep each other a secret, Anna smiles. This is sort of like avoiding what happens in Kiki’s Delivery Service, where Kiki gets to know Tombo one-to-one, but as soon as Kiki sees Tombo casually with his friends, Kiki dies inside.

- Explaining the three questions + Marnie’s brief disappearances

-

On the second meet up, Marnie proposes to Anna that they each will ask three questions to each other. Why? It’s because Marnie knows that making friends involves the awkwardness of negotiating between oversharing and undersharing, and so it’s better to formally stagger things out. This demonstration of self-awareness pleases Anna very much. Now Anna really has her trust. When Marnie asks

what’s it like living with the Oiwas

as a follow up question, Marnie disappears when Anna tries to think about them. So, in addition to knowing she only appears at high tide, we now know that Marnie’s presence is dependent on Anna’s frame of mind—her frame of mind cannot stray far outside the universe of her and Marnie. She reappears again when Anna recovers her thought process.

Anna, I don’t feel so good… The same things happen in the silo scene, which I will touch on later.

- Explaining the house party and hair pin

-

I don’t know if there’s much to explain here other than to highlight that this is where Anna and Marnie’s experience of each other is at its most vivid, and that Marnie unmistakably recognises Anna as Anna and not someone else, which is important to understand when later discussing the reality of Marnie and how these events are recounted in Marnie’s diary.

Anna ventures out and, again, meets Marnie at high tide. Marnie lovingly gives Anna boat rowing lessons, learn about each other, and relish how secretive their relationship is. Many details about Marnie’s life comes all at once here. Marnie disguises Anna as a flower girl and brings her into the Marsh House. We are introduced to her two parents, her

nan

, and her cousin Kazuhiko. Anna gives jealous looks when Marnie dances with Kazuhiko. Marnie, recognising her jealousy, gives Anna a moonlight dance.The next morning, Anna visits the Marsh House at low tide to find it’s strangely abandoned again. Nevertheless she spends the rest of the day doing housework, where for the first time we see her casually smiling. Marnie is in her heart. Anna momentarily loses her smile when Setsuko talks about how much her foster mother must love her. Anna is not convinced. Setsuko later remarks Anna’s hair has grown out, and so by the end of this scene, she is wearing a purple hair pin. What does this hair pin represent, other than the fact that Anna’s hair is longer? It represents Marnie (as we precisely learn later), and that she has Marnie on her head.

Hair pin of love. - Explaining Sayaka’s arrival

-

Anna races to the Marsh House when she realises she should be meeting Marnie again, but finds it’s still abandoned. Next day Anna is outdoors sketching, where she meets Hisako, who is painting. She clues us in the possibility of Marnie being real mentioning Anna’s sketch looks like someone she knew. Her coincidental interest in the Marsh House gives us an idea that something is auspicious about it. Anna heads there after learning someone is moving into the Marsh House.

Anna has a normal conversation with Hisako. Let’s just note for a moment that Anna has now demonstrated some social skills. Marnie has given her strength to begin socialising. She is healing.

So she meets Sayaka, a girl moving into the Marsh House. Sayaka thinks Anna is Marnie, because of a diary she found that aligns with her own observations of Anna wandering about alone. Now we’re clued into how Anna must appear when she’s experiencing Marnie. We at least now know she isn’t being physically transported to another dimension. Anna, baffled, explains she is not Marnie, prompting Sayaka to investigate further.

Anna read the diary for a bit, which describes events like Marnie rowing… alone. And a party where she invites… a flower girl. She doesn’t name Anna because she ofc wasn’t there, not time travelling, it was an actual flower girl. Although when reading it, Anna flashbacks to when she was the flower girl. Anna reads until she reaches torn out pages.

Anna and Sayaka are so cute together lole. - Explaining Anna and Marnie’s final day out

-

The next morning, Anna meets Marnie. The setting here appears to be her dream mode, but is it? I don’t know.

Smoky and low tide, it’s like a dream. Our two love birds hold each other, and Marnie admires the sketch Anna did of her. Marnie mysteriously explains she cannot go very far from the Marsh House, and so Anna accepts she will take lead on where to go. They walk across the marsh bed in low tide, which doesn’t seem possible because Marnie only appears at high tide. It now cuts to them mushrooming in the woods. Things aren’t so dreamlike anymore, so if she was dreaming, she isn’t anymore.

- Explaining Anna and Marnie’s final secrets

-

There is a lot to take in here. Let’s approach this carefully.

As much as Anna loves Marnie, she is now head-on intimidated by her when she talks about how wealthy her parents are. Even though what Marnie talks about is questionable, the way Anna reacts makes it clear how her relationship with Marnie isn’t perfect. Deep down Anna is frustrated, but doesn’t want to confront her.

Anna sulks rather than confronts. In a weird kind of retaliation to this, Anna becomes so desperately frustrated that she resorts to pity tactics. She can’t confront Marnie head-on, she uses an alternate route to either force Marnie to be guilty about her fortunes or concede her life is not that good. Anna plays risky and and reveals her deepest vulnerablility. She says she’s a foster child and that she cannot forgive her parents for leaving her. Now, Anna is used to her thoughts and feelings being trivialised: as much as she trusts Marnie, here she’s bracing herself for a stupid response. Fortunately Marnie’s response is effortful: she straight up poses a thought experiment,

if you really didn’t have any relatives left, then the folks that took you in must be truly kindhearted people.

Anna judges this as an ignorant response, but again, an effortful one, and so follows a pause of silence. She adds that they’re paid to care for her. When Marnie supposes

that doesn’t mean auntie doesn’t love you,

Anna’s pent up anticipation for a stupid response is let loose, sputteringseriously?!

But her anger quickly melts into sadness, explaining her situation is unique, that she can’t bear to see the anxious looks in her mother’s face. Marnie holds her, promising she will love her forever.

<3 Anna asks Marnie

it’s time for you to tell me a secret.

They’re still playing questions game! Marnie reveals that her parents are absent most of the times, and she’s bullied by the house maids. In particular, Marnie is constantly threatened to be locked up in the nearby, delapidated silo. This threat might be hard to appreciate; I liken it to the threat of being locked up in a shipping container. This makes Anna legit mad, but in actually in a healthy way, where she can actually confront Marnie. - Explaining the silo scene

-

Anna takes Marnie to the silo so she can overcome her fear of it. Anna is in control now. No longer does she feel submissive to Marnie, but an equal. On the way, Marnie mysteriously calls Anna

Kazuhiko

and walks ahead.From a distance, Sayaka interrupts Anna saying she found some more pages of the diary. These diary entries concern the existence of Kazuhiko. Do the recovery of these pages bore relation to Marnie suddenly referring to Anna as Kazuhiko? Will explore that in a bit. Also, the fact that Sayaka is present goes to prove that this scene definitely isn’t a dream—at least by now that is, but I maintain the possibility that it may have started as one.

Anna turns to Sayaka, then looks ahead again to see Marnie is not there. Her frame of mind has been disrupted, just like that scene when Anna was trying to remember who the Oiwas were.

Marnie calls Anna Kazuhiko.

Sayaka arrives with recovered pages of the diary.

Marnie disappears. Anna enters the silo to finally find Marnie again, trapped above. Again, Marnie confuses Anna as Kazuhiko. She’s also wearing Kazuhiko’s coat. Marnie finally recognises Anna as Anna and together they hold each other through the storm.

Where did that coat come from? Hmm… The way Anna’s frame of mind shifts here now has a permenant effect. Anna falls asleep and we’re shown a hazy sequence where Marnie is rescued from the silo by Kazuhiko. This isn’t Anna’s dream, this is just something viewers are learning indepedent of Anna. The narrative is ahead of Anna here in knowledge.

Ah, that’s where the coat came from. Anna wakes up and finds Marnie is gone. How does Anna react to this? Remember what I said of the opening scene, were Anna is crushed when a interaction with a teacher turned out to be a lie. Here, this is more than just a teacher abandoning her. This is a house of cards collapsing; every interaction with Marnie she ever had was a lie. What happens here is nuclear fission, where the consequences of this set off an uncontrollable chain reaction that makes out her entire life to be a lie. Amazin, well and truly.

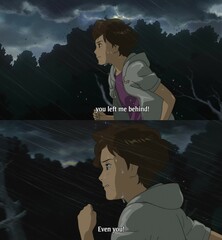

Everyone is always leaving Anna behind. Even you,

Marnie.Even you.

- Explaining the apology scene

-

Anna gets out of bed while still in her nightdress to confront Marnie. I thought this was a dream, but actually this happens for real in the book and doesn't sufficiently look like Anna's dream mode. She at first stubbornly decides she will never forgive Marnie. Marnie pleads for Anna to forgive her for leaving her at the silo, explaining

you simply weren’t there

, and thatI can’t stay here any longer

. Anna, although confused, tearfully forgives her. This is a deeply moving scene, for what Marnie really meant byyou simply weren’t there

is that is that in death, she couldn’t be there at all. Marnie managed to indirectly make Anna forgive her for that.

Marnie begs for forgiveness.

Anna forgives Marnie in more ways than one.

Everything clears when Anna reaches closure. The poingancy of

you simply weren’t there,

is the statement of closure that completely heals Anna, without her even directly knowing it. She wasn’t abandoned because it was something that was her fault, but simply because someone simply wasn’t there.

Marnie’s reality and timeline

-

What is Marnie to Anna; is she some kind of ghost appearing to Anna, or

is she

real

and Anna is shifting between dimensions? -

In the most indisputable terms: Marnie is a memory. The Japanese title of the movie is Omoide no Marnie, transliterally

[My] memories of Marnie

. The book actually wraps up the reality of Marnie in the very last sentence of the very last page, that Anna hadremembered

her.So that much is certain, but it doesn’t tell us anything specific. It vastly narrows things down; we know what a

memory

is and isn’t, so we can respectively develop and exclude further theories as appropriate. Let’s exclude a few first.I exclude the idea that Marnie is a

ghost.

Calling Marnie a ghost is quite a stretch, it’s the idea that she’s physically materialising in front of Anna… along with her maids, parents, Kazuhiko, and the entire setting of the Marsh House? That all alone is not likely, but also, how does it help to explain moments like the silo scene, where Marnie briefly confuses Anna for Kazuhiko? Or when Anna thinks of the Oiwas’, which causes Anna disappears to Marnie? Ghosts need to have some consistent balance of reality, otherwise it becomes something else entirely. Nor do I think Anna is being isekai’d, that she’s entering an unstable fork of Marnie’s timeline. How does this dimension almost-accurately reproduce Marnie’s past while, again, have this inconsistent balance of reality? And wouldn’t Anna’s mere presence in a fork of Marnie’s timeline cause the butterfly effect, and chaotically altering all subsequent events from the beginning?It especially isn’t plausible Anna actually time travelling. Anna does not change the past; there is no account of her in the diary. I briefly thought that the flower girl that Marnie wrote about in the diary might’ve of been Anna, but I now believe it was an actual flower girl (for reasons I’ll explain later).

It is understandable why throwing these ideas out might be upsetting, because it’s satisfying to believe that Anna’s interacting with a sentient entity, which makes her feelings real rather than a part of a delusion. Do not worry though, there are some other better ideas to look at that doesn’t make out Anna to be a total schizo.

After all, it is important to note that there still is a

two-wayness

to Anna and Marnie’s interactions; when Anna disappears to Marnie, when thinking about the Oiwas, this scares Marnie and time to her appears to have elapsed. - Is Anna’s experience of Marnie a reconstruction of the stories she was told as an infant?

-

Having established that Marnie is nothing but a

memory,

you might think that directly confirms the theory that Marnie is a reconstruction of Anna’s childhood memories of stories told to her at her bedside by Marnie herself. Nope. This theory is not consistent with the book. The book does not cast back to her infancy with a scene like this.Anna’s experience of Marnie doesn’t have to necessarily be an autobiographical

memory,

it’s still open to being something on the side of spiritual or ancestral. At the most we are assured that her experience is something like a very vivid recollection. - Is Anna dreaming?

-

Partially. There are very short, limited moments where its certain Anna is only dreaming of Marnie: in the initial scenes where Anna merely dreams a girl with blonde hair she sees through the Marsh House window. These scenes are distinctly Anna’s dream modes, as I discussed in the plot summary; smoky and half tide marsh bed. Although I clarified the apology scene is not a dream, the weather dramatically clears to clear and sunny, representing Anna’s sudden sense of closure. This is sort of dream logic. So I suppose it could be a dream, if not liberties taken with animation.

This alone strengthens the case that the existence of Marnie is something internal to Anna rather than materially existing, or you’d otherwise have to build a case that there is something affecting both Anna’s dreams and reality.

But, are all Anna’s experiences of Marnie just a dream? No. Making this case would start from the idea that Anna have a pretty severe sleeping disorder, that she’s dangerously sleepwalking the whole time, sometimes found on the side of the road. But also, remember how Sayaka disrupts Anna when she’s heading to the silo. That’s certainly not Anna having a dream—one can’t even argue that she’s also dreaming of Sayaka there too because we see in a later scene, Sayaka back at (now, her) Marsh House mulling over the diary in the context of having seen Anna earlier.

It should be noted that Anna’s dream mode does not seem to substantially reflect any of the historical experiences of Marnie.

- Is it all otherwise one big fabrication in Anna’s head?

-

Yes and no. It’s not all a big fabrication, just partially—like Anna is wearing VR headset that’s altering what she sees. If it was

all

, then this basically would be a variant on the dreaming theory. It would be unusual to imagine so almost-accurately, things that actually happened decades earlier. - Is Anna a stand-in for Kazuhiko the whole time?

-

No. This theory is meant to help explain why Marnie is so romantically inclined to Anna, and why Marnie briefly mistakes Anna as Kazuhiko in the silo scenes, where the illusion is breaking down. It entirely forgets however that Anna saw Kazuhiko at the house party—who was Anna to Marnie then? Perhaps you believe that Anna was a stand-in for the actual flower-girl in Marnie’s timeline in that scenario. Not true either. A replacement, yes, but not a stand-in where Anna looks like someone completely different from Marnie’s perspective. Marnie in these scenes perfectly recognises the disguised flower girl as Anna in continuity to all the other scenes. This logic will be discussed in more detail later.

- Is Marnie a spiritual projection?

-

This is the idea I have managed to successfully flesh out the most and will advocate. This theory was first outlined by Vincent Kavanaghvk, who proposes that Anna’s experience of Marnie is

a spiritual overlapping of timelines,

prone to being interrupted. He fella also partly incorporates the idea that Marnie is a ghost, which I don’t agree with, but nevermind that for now. I have illustrated this idea here:There are three things here. Anna’s spirit, Marnie’s actual timeline, and Anna’s experience. Anna’s spirit imperfectly projects itself onto Marnie’s timeline of things that actually happened. Historical Marnie would spend time outdoors alone, but Anna overlays this timeline and becomes her friend. If Anna’s frame of mind is disturbed, such as when she begins thinking of the Oiwas’, then Marnie disappears. Or when Sayaka disrupts Anna as she heads to the silo, again, Marnie disappears. These disturbances are why the projection is imperfect.

This also supports the two-wayness of Anna and Marnie’s interactions too. In the former scenario where Anna thinks of the Oiwas, Anna likewise disappears from the perspective of Marnie, so things fallback to her original timeline where she is alone—Marnie’s days outdoors alone are documented in the diary. Marnie’s sudden loneliness frightens her. In the latter scenario, the silo scene, in fallsback to her original timeline where Marnie is with Kazuhiko, so it’s a bit more a seamless transition to Marnie in a way she doesn’t fully realise.

- Is Marnie a tulpa?

-

This is a fun idea I credit to a friend of mine. Some background: a tulpa is an imaginary friend you imagine so hard that it becomes an separate sentient entity in your head that indepedently talks and has its own thoughts and feelings. It fully becomes a two-way thing. People have claimed to have done this irl, especially those in the My Little Pony fandom who bring characters from the show to life.

Anna became so lonely that she began to construct an imaginary friend, a tulpa. This tulpa then began to attach itself to the spiritual aura surrounding the Marsh House/diary in her proximity and began carrying out Marnie’s most traumatising and beautiful past events. This tulpa is two people,

Anna’s Marnie

and thehistorical Marnie

. Marnie is Anna’s friend when Anna is focusing, but becomes historical Marnie when she’s not focusing straight, therefore confusing Anna as Kazuhiko at one point.And then, this tulpa began presenting itself in vivid situations. This can be integrated into the spiritual projection theory.

- Is the diary a Horcrux; are the writings of the diary being summoned?

-

This is a theory proposed by video essayist Megan, who suggested that the diary is a horcrux; the diary literally contains the memories of Marnie, but is enchanted in a way that Anna’s proximity summons it, causing her to experience what’s written in it. This simultaneously explains why Anna can’t stray too far from the Marsh House, and explains that Marnie’s eventual disappearance would have been caused by Sayaka’s tampering of the diary.

This is a pretty fun idea, characterising the diary or the whole Marsh House itself as a horcrux is useful for the spiritual projection theory. It explains where Marnie’s timeline is coming from in the first place.

- In conclusion?

-

Marnie is a memory conjured as a spiritual projection overlapping Marnie’s timeline, possibly chanelled through a horcrux, possibly presenting as a tulpa.

Anna and Marnie’s relationship

- Are Anna and Marnie in love (gay)?

-

Yes. They are in love. Beyond reasonable doubt, they are so in love. They are moving bare fruity still. I understand there maybe some reservations about being so enthusiastic and certain about this. I will address that matter, but first please just consider what happens in this movie at face value.

- Anna backs off when other girls begin to talk about boys.

- Anna moans Marnie’s name in a moment of fright.

- Anna blushes at every tender interaction with Marnie.

- Anna draws detailed portraits of Marnie.

- Marnie pleads that their relationship be kept a secret.

- Anna is jealous when she watches Marnie dance with Kazuhiko.

- Anna and Marnie exchange I-love-yous multiple times.

-

Their relationship is probably

innocent

to Japanese eyes and everyone else is misinterpreting it; westerners falsely interpret any kind of intimacy as romantic, no? -

A blogger said the following:

I feel it is a cultural difference. I think people in the US are, on average, much less heteronormative than the Japanese, so we are more likely to consider a gay subtext as valid.gb

This is forgetting that Yonebayashi and Studio Ghibli didn’t write this story or create these characters. Joan G. Robinson did. Remember, the movie was adapted from a book.

So the real question is,

did Yonebayashi accidentally adulterate this story with perceiveable yuri themes?

Here is the answer, and it’s quite extraordinary: the book is more gay than the movie. Yonebayashi toned down the yuri themes from the source material. In the book, Anna and Marnie are fairly physical with each other, and Anna is far more emotionally needy towards Marnie. Don’t just take my word for it though because the handful of people who have bothered with the book after the movie, some I’ve become friends with, encountered the same shock.od I mentioned the book being a favorite of mine among my coworkers. One colleague, whose in her late 40s, said it was a favorite of hers when she was a child and that she had read it with her daughter. She didn’t flinch when I said it’s the greatest homoromantic novel ever written.All this being said, it doesn’t fundamentally matter either way: the queer theme in this story isn’t very serious. This isn’t San Junipero. Believe it or not, you can have queer relationships in stories without the queerness being the exceptional component. There’s a lot more going on this this story! I just ask that people recognise the actual depth and sincerity of their relationship at face value, rather than invent these excuses.

- Isn’t this sexualising the characters; the book was published in 1967 and so couldn’t have queer characters.

-

Nope. There is an awfully egregious assumption that any queer relationship is necessarily sexual. Indeed, I have read film reviews by writers who, while obviously not having read the book, go straight ahead in mentioning that it was written in 1967 and therefore it isn’t queer—fullstop. For example:

The reason why When Marnie Was There never had a shot at being an LGBTQA story is because it’s based on a mainstream British children’s book by author Joan G. Robinson, published in 1967. British censors at the time would never allow the unedited release of a book, let alone a children’s book, that promoted positive portrayal of LGBTQA people.cbr

The book had no reason to be on Mary Whitehouse’s radar. What kind of books were being hunted down then? One example of a childens’ book that was contemperaneously censored was The Little Red Schoolbook (1969), a book written by Danish schoolteachers on how to defy authority. That book had a statement. That book was conciously countersignalling social norms.

If I had a time machine I’d show Mary Whitehouse the pain olympics. This book, however, was not countersignalling anything that might’ve got it censored because homophobia then was largely confined to the scope of banning lewd magazines and cottaging, not (yet) a prevailing social conciousness about homoromanticism. I’m not saying the 1960s was less homophobic, absolutely not: what I’m saying is that only our present social conditions make Anna and Marnie’s queerness notable because it exists in contrast to the history of homophobia, whereas in the 1960s this happened not to be a target because it would not be an immediate concern.

So all this is like debating whether not Toichi is mute, because in some alternate universe being mute is taboo. Is it not enough to independently consider what actually happens in the story?

I’m yet to find reviews of book that are contemporary to its 1967 publication. The Wikipedia article for A Wizard of Earthsea assures me that British literary critics of the 60s and 70s were open minded to children’s literature. The British Newspaper Archive doesn’t yield anything as far as local newspapers are concerned, so it’ll warrant a trip to the British Library one day. I of course don’t expect there will be queer discourse, but I do expect their relationship will be characterised in some way or another.

- If Anna and Marnie are gay for each other, wouldn’t that mean their relationship is incestuous?

-

Yes, but only romantically and not in any meaningful way. Just because Marnie is Anna’s grandmother doesn’t mean their romantic love becomes undone—in fact, the source material doubles-down on incest themes by having Kazuhiko (

Edward

) be her cousin, who she marries in later life. If the source material is content with biological incest, what’s stopping there being a little bit of romantic incest.Maybe their relationship is latently sexual. In theory their relationship has the potential to fit the complete definition of incest, though without the moral issue of consanguinity because it’s same-sex. Well, as we know, Marnie leaves forever in the end, so all we can actually consider is how Anna feels towards Marnie. We can only imagine! As she grows up, with those unresolved feelings…

But please appreciate how tenuous and restricted that line of reasoning is, and how it’s left the boundaries of the story and ventured into headcanon. My point is that as far as the story itself is concerned: it doesn’t matter.

I am surprised that this is such a big deal, because Anna and Marnie’s blood relationship is merely a technical hurdle, not a practical one: there is no grandmother-granddaughter dynamic being subverted, there is no physical age difference, and they are as good as any coeveal couple. Let’s be pragmatic about this.

-

Is Anna transgender?

-

Her tomboyish, perhaps all-out androgynous appearance in the movie is because of a quirk of how the source material was interpreted. There is a line where Marnie lols at Anna’s

boy clothes.

Not because she’s literally wearing boy clothes, but because the timeslip is being hinted at: Anna’s 1960s clothes look bizarre and androgynous to Marnie’s 1910 clothes. I don’t know if it was the Japanese translation of the book that’s the cause of this, or how Yonebayashi interpreted that part with (understandably) not much knowledge of the history of anglo fashion.It has been very convincingly argued that Anna represents the transgender experience however. As a Letterboxd review had explained it:

[c]ertainties other kids take for granted (like the fact that mom and dad love them) are rendered uncertain for queer and trans kids.

This is a pretty beautiful way of looking at it.

Comments

Oh, it’s impossible to completely explain Marnie. There's so many open ended

parts of the story that I entirely concede to being totally ambigious. There

are parts I’m not sure whether Anna is dreaming, and there are numerous

merely possible theories that can be combined. I summed it up myself to a

friend, sometimes you have the love the questions themselves.

I think, personally, I put in a lot of effort in looking at the emotions and characters because that’s what means the most about this movie to me. I first watched Marnie at a time in my life where I totally lost the ability to be vulnerable to anyone and it deeply moved me.

- When Marnie Was There - Japan and US Trailers comments Hayley Harrison

- When Marnie Was There: Ghibli’s Final Film Was ALMOST a Queer Classic Anthony Gramuglia

- Thank You, Anna! But Our Ghostly Girlfriend is in Another Mansion (When Marnie Was There) comments superhappyawesome

- A childhood story – further thoughts on

When Marnie was there

Clara Bridges - When Marnie Was There: EXPLAINED Vincent Kavanagh

Updated, 17 January, 2025. Changed various references to Anna arriving in "Hokkaido".