Born 10 February 1910 as Joan Gale Thomas in Buckinghamshire. Her parents were nonconformist protestants who lived in the late Victorian times, who grew up circa 1880 maybe. Her mother in particular had childhood memories of druken street brawls in Hampstead, where she was born, so she was determined to keep her family safe by settling somewhere peaceful and quiet: born in Gerrads Cross, then raised in Hampstead Garden Suburb, then Letchworth Garden City—a once teetotal, planned community initially founded by Quakers before being developed into a town.

Robinson resented her sterile, boring life in the suburbs. Indeed, she and her family lived down a close; no one came through, so staring out the window didn't even yield the pleasure of watching life passing by. Alas, she retreated to books, indulging in stories of children who had cool lives. Robinson went to seven schools and did not pass any exams, because schoolwork was meaningless to her—a fact that is much recounted in the few, scant, accounts of her life I found of her, by the way.

Her relationship with her mother is fascinating; so much so that I won't spoil all the details now, for they must be left to my discussion of Marnie.

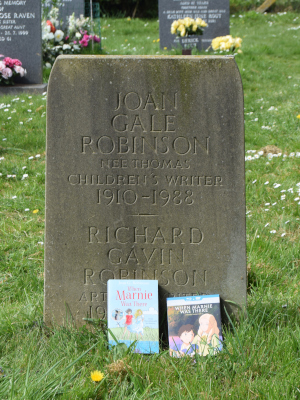

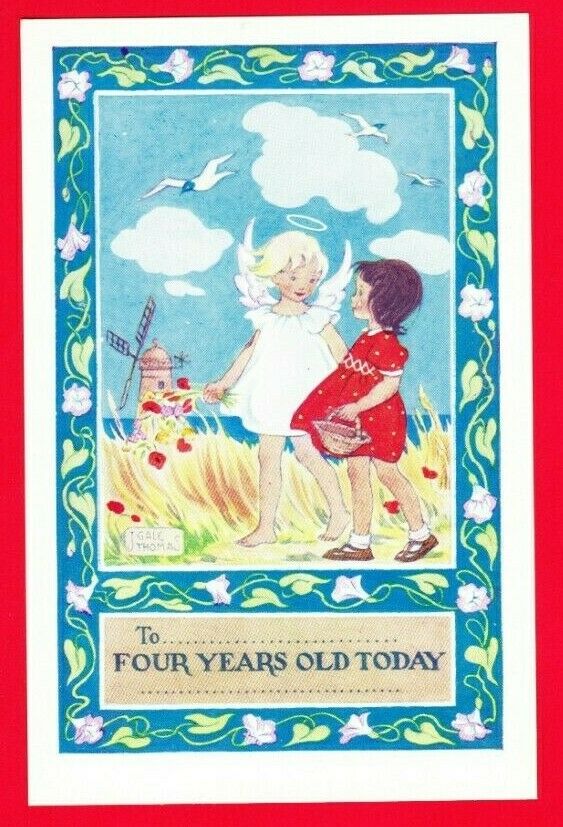

Robinson began producing published works in 1939, when she was about 29-years-old, and before she married to Richard Gavin Robinson in 1941. She submitted Christmas card designs to Mowbrays, a publisher that specialise in Christian art and literature (who are still operational by the way). To her surprise, they liked it and had it published. There she continued with birthday cards, and then eventually books—or rather, booklets, aimed at small children for Christian instruction. She did these books with her husband, who did the principal outline drawings, while Joan did the writing and put expressions on the faces. Richard Robinson was apparently an author too, but cba to find any info about him.

Curiously she continued to publish these booklets under her maiden name Joan Gale Thomas

despite being married at the time. It is unclear if she was using this name as a thin pseudonym, or if it's just that she didn't take her husband's name some years later.

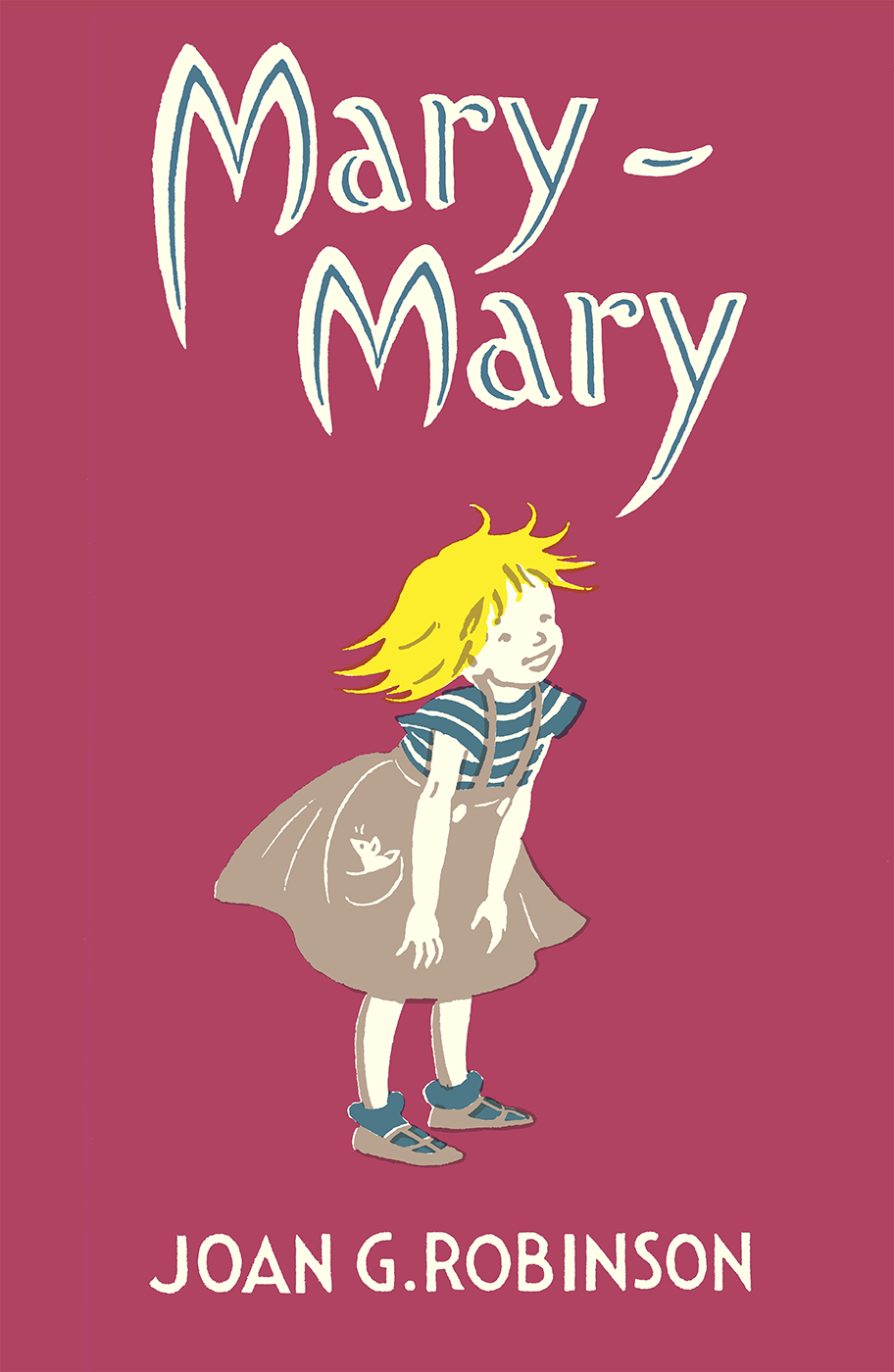

Circa 1950 she started to write and illustrate secular material, still squarely for small children (Teddy Robinson), but over the years spiraled outwards in scope of subject matter; books for somewhat older children came circa 1960 (Mary-Mary) and then Marnie came in 1967. She did a few more books, becoming popular enough to have done a book signing in 1974. Her last book was published in 1978 and she died in 1988.

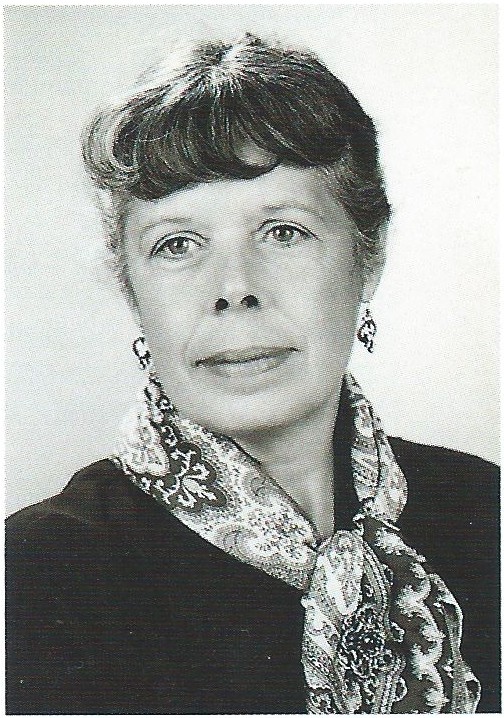

So her first thing she did was a Christmas card design in 1939. What did it look like. I don't know, but I found this nativity scene she did, which looked a bit like a woodblock print. She later went onto doing birthday cards for 2-year-olds, 4-year-olds, etc. The works she did during this period is best archived by the University of Southern Missisippi in the United States. Why them, I don't know, but I found their library website claims to archive her manuscripts.usm

I found Robinson in the 1940s did a Christian themed birthday card, which I noticed included seaside scenery, sand dunes, and a windmill. What could such provenance mean? Maybe not much, she made no secret of having a life-long connection to Norfolk and such scenery, but I like to think it planted the seeds of her publishing career.

Her first booklet, A Stands For Angel, came in 1939. Read that again, it's A

as in the letter A

. Not the English grammatical indefinite article a

. I was confused. It's an alphabet book themed around Christianity. Hm. Yeah, that's. Good stuff. According to an interview with Robinson in 1969, she put on a show of embarassment about this period of her work, giving no explanation as to why.

More of the same was churned out at low volume until 1953, when she wrote Teddy Robinson, a book about a teddy bear, a girl, and their make-believe adventures. For a little while the books appeared to dominate her legacy. Or maybe even the whole while, from one perspective: an obituary of Robinson notes that Teddy Robinson became family lore in many households, and in such circles firmly became the only thing known of the author. But of course Robinson herself, and everyone today, believes that Marnie is her greatest work. That's because it is.

The title for two books, published in 1957 and 1958. Each an anthology of short but loosely chronologically connected stories. The book I got was an omnibus of these two books, published in 2013. I wonder if it was in anticipation for the Ghibli film for the year after, with the expectation that there would be an uptake in the book and therefore Robinson's works in general. Each story involves the titular four-year-old girl getting into ridiculous household antics that at first seem to vindicate the view of her siblings, she being the youngest among them, that she's silly and musn't be taken too seriously—her name is actually Mary, but they call her Mary-Mary cause she's always so contrary. In the course of her ridiculousness though, she always goes full circle and proves herself to be clever in the end. Like the life of Timothy Dexter innit.

The stories center on pleasant circa 1950 British domestic family life. A brother who goes fishing. A sister who practices scales on the piano. Story-by-story, one incrementally gets to know the other cast of characters, like family friends Barbara and Bunty. There's a lady next door who's happy to invite Mary-Mary into her garden without anyone else's permission. Most provactive of all, there's a kind man across the street who takes Mary-Mary to the cafe on a whim, without permission. A character no one would even dare write now, let alone happen irl, cause we're all noided of nonces now.

You naughty girl!they all said together.

We’ve been looking for you everywhere.[…] Mary-Mary shut the door. Then she said through the letter-box,

You shouldn’t shout outside other people’s houses. I’m ashamed of you.

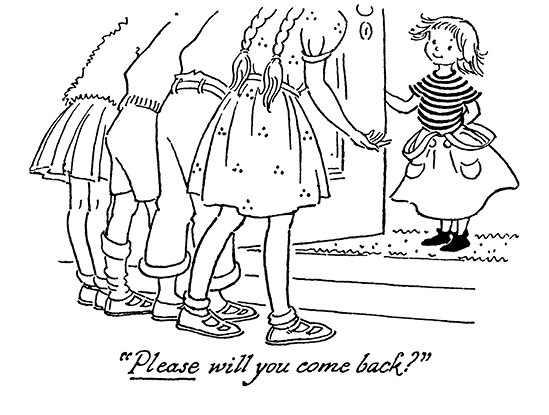

One of my favourite moments of the book is when Mary-Mary goes visiting

, her roundabout way of running away from home after being ignored by her brother and sisters. When her siblings finds she's at a neighbours house, they plead at the doorstep for her to come home, to which Mary-Mary wordlessly closes the door and basically says through the letterbox no

. It made me burst out laughing because of the comic timing, perfectly imagining them exchanging baffled glances as she closes the door, and the awkward two-second silence before her stupid eyes pop out the letterbox.

The illustrations are simply lovely. I was blown away when I first saw illustrations from its feature in MOE, which is what motivated me to have a serious look at Robinson's art. They're strangely modern looking; a vibe I get from a lot of mid-century art and design. Clean and simple lines, and figures consisting of shapes that lend themselves to bold blocky colour schemes—just take a look at the front cover of the 2013 book, for example.

These are the most details I can bring to the table for someone who only knows of Robinson through Marnie. The kindly social life that present in Marnie, merely placed out of reach for Anna, is present here and placed in the middle of all the action. It's so freaking adorable, sweet, and funny… reminds me of Yotsuba&! in that respect. The stories are for young children, but not very young. The writing is a bit syntactically simple, but the plots go in clever directions and aren't always predictable.

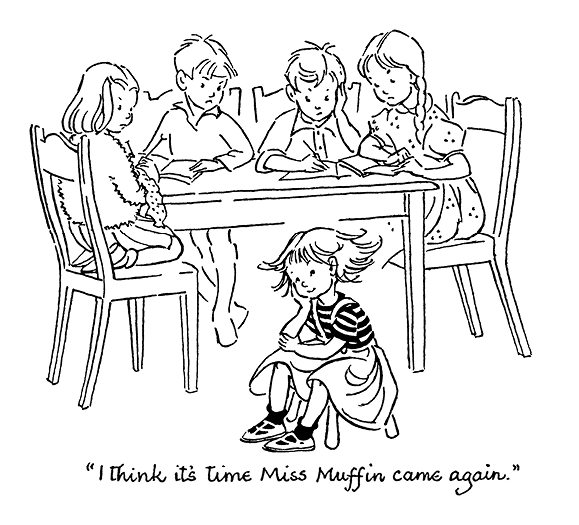

[Mary-Mary] said in a dreamy voice,I think it’s time Miss Muffin came again.When Mary-Mary said this everybody groaned, because they knew what it meant. It meant that Mary-Mary, dressed in some of Mother’s old clothes, was going to come knocking at the front door, saying she was Miss Muffin and had come to tea. Then everyone had to be polite to her and ask her in and treat her as if she were a real visitor. If they didn’t Miss Muffin made such a scene, marching up and down in front of the gate and shouting thatsome people had no manners, that they were all ashamed of her and had to hurry out and bring her indoors before a crowd collected.

Duh! Published in 1967.

I once visited the Jane Austen museum, the house where she lived at the end of her life, and one exhibit detailed the publication history of Pride and Prejudice. The book was intially very popular around the time of its first publication, but became quite forgotten for decades after Austen's death. It was later revived for another print run from renewed interest in the story and it hasn't been out-of-print since. Indeed, it's a world classic now. This had me thinking: could there be such a chance for Robinson? It's almost criminal how forgotten Marnie became, let alone the rest of Robinson's works. Maybe there isn't a chance. For as long as draconian copyright law will persist, at least. The book will not go public domain until 002058 AD. Cool.

While I've written plenty about this book before, I suppose it's worth discussing its place in Robinson's chronology and how it came about. Though I also wrote the Wikpedia article detailing all that stuff, I have some additional thoughts and feelings beyond what can be put there.

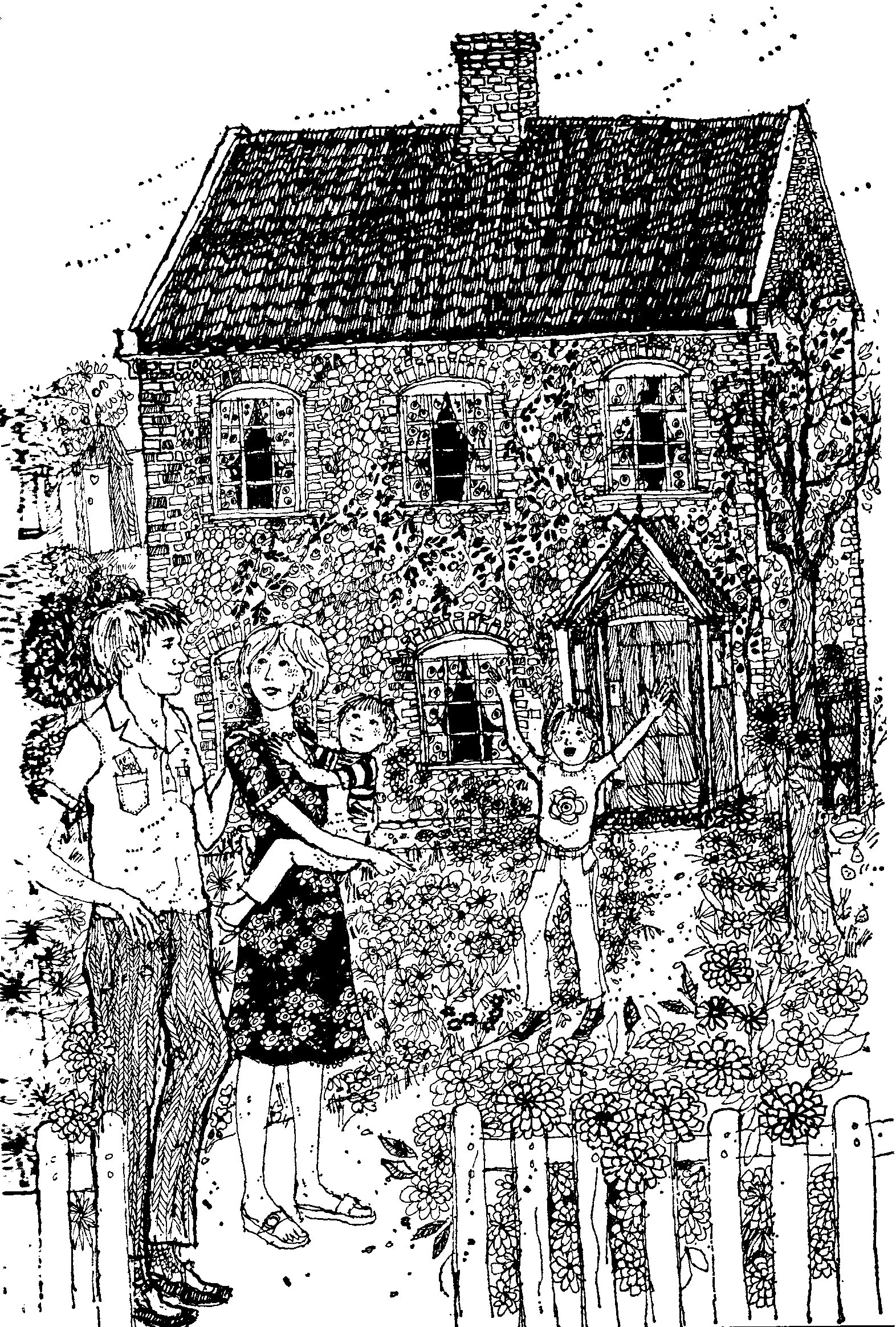

If you read the post-script of a modern edition of the book, you'll have heard the story about how Robinson was first motivated to write the book. When she was having a holiday in Burnham Overy Staithe, there were two principle things she observed: the elusive appearance of a building in the low light, and a girl having her hair brushed. From there she began taking notes, developing characters, writing plots, eventually synthesising it all into a manuscript.

So that story about Robinson's inspirational evening at Burnham Overy is pretty nice, one that firmly establishes the connection between the story and real life location. It leaves one wondering why though, Robinson wrote the characters she did, and why the story's conflict is what it is. I become desperate to find an some kind of interview with Robinson. It began with me finding and this 1,000+ page encyclopedia from the 1980s on childrens' book authors, which had remarks by Robinson talking about her works.

This was a pretty thrilling start to things. Next came a library enquiry, generally asking for reviews or interviews, suggesting Naomi Lewis, who contributed to that encylopedia, might have done done something elsewhere. The librarian replied saying they did not find any interviews, but they did indeed find a book review by Naomi Lewis. Hell yeah.

This wasn't enough though, from there I decided to make a trip to the library to look further into this, among other things. Spoke to a few people. First discussed the sort of stuff I was wanting to research with some guy who assured me that the 60s and 70s are basically current

and there's a chance there might be audio interviews with Robinson, which secretly I highly doubted but smiled and nodded anyway. Other person suggested I look into The Guardian and The Observer newspaper archive. This is where I would hit the jackpot. First The Observer:

I found this exceptionally charming, sentimentally satisfying end and all.

— The Observer

In addition to all this, I had a few leads of my own. I figured to look into this old and oddly generically titled magazine, Children's Book News. You see, with my copy of Charley the back cover quotes a review from it, so I figured it probably reviewed Marnie in the past too. It did interestingly enough, only in a minor way though—it was more of a publication notice than a full review:

This is a deeply perceptive study of lonely Anna, a foster child surrounded with well-meaning kindness, none of which touches her real self.

— Children's Book News

You're like a mother to me

The most fascinating article I found was an interview done by Robinson in 1969 with The Guardian. It is simply amazin, more valuable than just helping me fatten up the Wikipedia article.

I am Anna of course, and Marnie is my mother. My mother was always un-get-atable. Without meaning to, she always let me down. I found this extremely difficult to forgive, for without realising parents are in the same boat as yourself, that they are children, too, you can’t forgive them for being frail and human. But until you learn to forgive, you yourself are crippled, can’t begin to grow up. Through writing Marnie I faced the truth and found understanding. It made things a lot better. — The Guardian

Robinson appears to suggest—just appears to suggest—that the relationship between Anna and Marnie is an imitation of her own relationship with her mother. This gives me a sense of threat towards my campaign of insisting that Anna and Marnie are in love, in the book and the movie, because this would suggest that in writing Marnie, Robinson logically progressed her feelings for her mother into an Oedipus complex. This consequence, I do not believe.

In 1971, there was a television adaptation of Marnie, by BBC1 London as part of the Jackanory book-reading series. This isn't just a bit of vague apocrypha that was dug up among old television listings, it was mentioned by Deborah Sheppard in that postscript she did for the 2002 and 2014 reprints of the book. Also, there are elderly people still living who can testify having watched it:

Jackanory introduced me to 'When Marnie Was There', which was the first book I'd ever read about an adopted person like me. It was so exciting!

—Kate Long on twitter.com. Unfortunately this person is a TERF.

I first heard [Marnie] read on Jackanory in 1971 by Ann Bell. I was 12 at the time and loved it so much my mum bought me a copy for Christmas that year. I still have it. Well read and still much loved.

—Trudy Franklin on twitter.com

Heard [Marnie] on Jackanory, found the book and loved and then lost track of it. Found it again on a second hand book stall and then the animated #studioghibli version came out in 2014.

—Jean Edwards yet again on twitter.com

This adaptation is lost, which unfortunately is typical of for a lot of television back then. The medium was designed to be purely live afterall, recording stuff and timeshifting was an afterthought. This adaptation did have another airing according to a 1973 listing, but that's about it, video reels were often taped over because they were expensive and britain the 1970s was very poor.

I can imagine somewhat imagine it though. It would've been black-and-white. It would've opened with actress Ann Bell sitting on some kind of chair introducing the story, and then cutting to film of the train station scene, then filming in Burnham Overy. Based on what Deborah Sheppard has said, there were some fairly sophisticated shots: there was some filming in a boat on the marsh creek, a serious logistical challenge for film and photography then. Jackanory had a fairly solid soap-opera like neorealism to its casting: the child actresses would've been amateur, but not necessarily bad, it's not like wacky and Shakespearian shifts of mood would've been demanded of them.

If you want a taste of British 1970s film and television of the kind of budget of Jackanory, I have recommendation: one of my fav films ever is Apaches (1977), which follows the misadventures of a group of children, and the performance of the actors in that were flawless. It being also a 70s production, I imagine it could've been something similar in calibre to that.

I can only imagine.

I don't want Charley, you know that…

Published in 1969. Anyone who has done some cursory reading of Robinson's background as a result of reading Marnie has probably heard of this novel: it is said that Robinson specialised in writing moody girls, and this sits next to Marnie in a chronological list of her works, therefore it registers in the mind that this must be one of those other novels. I was prepared to not like this book, because I didn't want to make it seem like Marnie is comparatively anything less than Robinson's singular perfect achievment, her magnum opus. Need to admit however that this is a very, very, good novel.

The story follows the girl Rowan, nicknamed Charley. She believes she was allowed to be abandoned, and so in a dramatic double-down she runs runs away into the gardens, fields, and copses of Market Barnham and surrounding Norfolk parishes. Actually, the exact reason she runs away is fairly complex and knotted up with other plot elements, in the exposition, but also throughout the story. It's an evolving premise, in the course of which Charley is forced to reckon with deeper aspects of her predicament: does she really live up to the romance of a free-spirited vagrant; was the school artwork prize she got real or a fluke; and what is her name, really—Charley

, Rowan

, or someone else?

On the surface, running away

sounds like almost cute and lightweight of a premise, but again it's a bit more complicated than that and it becomes pretty high action—lots of places and range of imagery, big and highly connected cast of characters, uplifting in some places and heartbreaking in others.

In a weird way this book is partly Daoist; as half-mentioned, one of the ideas explored is the value of a True Name. This might be the reason why the alternate title for this book is The Girl Who Ran Away, because the book isn't just about a girl nicknamed Charley, but the girl she was, and the one she becomes while out in the woods. I would title it Lest a Bird Die of Thirst, a the title of one of the chapters I happen to like.

In chapter 20, someone to talk to

, Charley learns who is tenant to the caravan by the copse and is responsible for the dog tied up by it, after being much eluded by it for days. It was a man—not a boy, as Charley had initially judged in his passing appearance in chapter 15—who too, had ran away, but not in the fashion running away

had so far meant in the story. His is, as we come to learn, John, son of Mrs Denning, and one could guess around 23-years-old. Early in his career and soon to start his first teaching job in the coming school year, he is anxious; he has a sense of dread over his new job, and isn't sure where life is heading for him.

Now while I don't think Robinson wrote Charley in mind for a 20-something-year-old audience, here she wrote a character with careerhood problems, adult-specific anxiety, and vulnerability, and immediately I wanted to tell everyone I know about this book, if only his existence wasn't a spoiler. My goodneess, the conversation that plays out between her and him: so again in chapter 20, Charley tells him she's a runaway, with a reckless pleasure that came with being able to actually talk to someone after all that had happened, no less to the guy whose dog she'd been caring for when alone. They have a friendly back-and-forth of questions in what becomes some sort of highly self-aware therapy session; she mentions her anxiety about her school art prize, and so he asks:

And are you using [your prize]?

Yes, here, I am. I couldn't at home.

No, of course you couldn't. Not with everyone expecting you to produce a masterpiece!

Eventually John just throws out there ya I'm like you

. This baffles Charley at first, and John challenges Charley to figure out what he means, and that's when he explains his own life situation, and that renting out a caravan is is way of escaping. They are both suffering from imposter syndrome.

The inclusion of John cemented my opinion that this is a book of comparable value to Marnie. Not merely one of the many relatable

characters Robinson wrote in her lifetime, but a character like me, a young working person. It gave me goosebumps to be seen. It's not such that I relate to John's situation specifically, mind you. It's rather that there was a character in the book that assessed Charley's situation the same way I, the reader, did too.

Throughout the book, Robinson explores what I can only call enclosure politics, to coin a term:† the high-level concepts common to the social and political problems of homelessness, travellers, and the settled. Charley, when she runs away, at first fancies herself to be a bit of a free-spirited bohemian. Having slept under a tree and washing her face in the dew, everything so far seemed perfectly magical. However, comforts increasingly become hard to come by. While out in town pretending to be deaf-mute to shopkeepers to obfuscate her identity, she drops the act for a bit when she comes by a girl along the road. This girl asks Charley who she is and where she came from, where Charley only then really admits she's a runaway—but, there's nothing to it

she cooly insists.

Her situation progressively becomes worse however, and she begins to wonder if she's in fact a charity case. A fatal blow comes the next time she encounters the girl at the Sunday school, Marilyn, as she now is come to be known as. There are many good conversations that happen in this book, and the conversation between Charley and Marilyn is one of the best and perhaps most potentially controversial. Marilyn says she doubts Charley is not any sort of vagrant; if Charley really lived underneath a tree, then she's a tramp

. Charley attempts to refute this,

Oh? What about gypsies then?

Marilyn shook her head.My mum, she say gypsies live in trailers round the scrap heaps.

These two lines made my jaw drop, before having to contain my laughter. It's one thing to perjoratively call her a tramp, but the casually scornful remark about gypsies being scrap heap rats is pretty wild. Could this book be printed nowadays? Clearly it wouldn't be enough to a little more politically correct and replace gypsies

with travellers

, nor would editing out this whole conversation suffice; Charley's dignity being indicted here, and that's important for the rest of the story.

This conversation rounds-off with a moment of pure cathartic delight that had me punching my thighs. Charley flexes her newfound mental freedom by issuing a hard comeback, delivered with enviable intuition: I don't need your mother's permission for me to exist.

Damn.

Oh, while on the topic on probably dated langauge, here's another thing. I found one Amazon.com review that questioned whether it was appropriate to represent rural English kids the way it did, like Marilyn herself no doubt:

It's slightly dated—particularly the slightly snobbish phonetic transcriptions of the village kids' dialogue—but still very enjoyable, very atmospheric, lovely characterisation.

Is this a problem though? I find it more charming than snobbish. A triumph, even, that the last remnants of English semi-rural childhood had been documented at all because no one talks like it anymore. Nowadays it's not a thing anymore, given the cultural osmosis between no-name shire towns and US flyover state kids whose shared aspiration is to become talentless e-celebs. The only accents around now is estuary English. A geographically faithful adaptation of When Marnie Was There couldn't be done anymore given the Norfolk dialect has died out.

So the reason why Charley runs away was provoked by, and centers on, her deterioriated relationship with her aunt, Marguerite Raven—also known as M

(Aunt Emm

)—a sour, bossy, and past-middle-aged woman made to live with Charley and her siblings (whose parents are barely mentioned and practically absent through the whole story). At the beginning we're force to reckon with how, while not amicable, how clean and skillful her discipline towards Charley's two brothers are, in contrast to how blundering and confused she is towards Charley herself.

A moment I enjoyed early in the book was when brother Giles, determined to trivialise Charley's school prize, reached for her paintbox obviously intending to manhandle it: Aunt Emm scolds Charley after shouting to take his bloody hand off it, language like that I will not tolerate!

she says with an air of satisfaction, like hell yeah, I got this. Of course the joke turns out to be that Giles' hands were in fact bloody, covered in blood, and the whole situation turns slightly awkward.

In combination to prior events and briefly following events (receiving that scrap of paper with I don't want Charley, you know that…

), that's how we get to know her at the beginning, and how we hold her in our thoughts throughout most of the story; Aunt Emm lives rent-free in Charley's head for the time she's on the run, resenting how such an unlikable person was so easily allowed to let her be abandoned. Her role at the end of the story is more fascinating however, when she comes to see Charley in Norfolk after the whole ordeal of her being found at the summer house in a shattered condition. She continues with more blundering, as Charley can't help observe her embarassing determination and tactlessness in finding someone to blame for her unintentional abandonment—of course not out of justice for Charley, but only to save face. Out to Right Great Wrongs.

Of course the situation is much more serious, and so precipitates into something much more sobering. In a private yet overheard conversation with Mrs Denning, who had rescued and gave amnesty to Charley after finding her in her summer house, Aunt Emm concedes she doesn't really know what's she's doing. That actually, Charley being a girl, she doesn't understand girlhood at all, having grown up being denied one herself under a man dominated life. The less flexible gender norms of her time meant that her own gender identity sheared out of shape: she admits her boy siblings denied her ever feeling secure with feminimity, but at the same time she had to make-do with the lack of opportunities girls and woman had.

I never could do with girls […] I never did understand them […] I only had brother's you see, four of them […] somehow we never seemed to come across girls.

But it's all so different nowadays. They're treated the same as their brother's, they have the same opportunities, the same education, even the same clothes.

[Mrs Denning asks,]Did you never miss the sort of things girls like? Pretty things?

[Aunt Emm laughs,]No, I had that soon knocked out of me […] I was soon laughed out of that!

So that explains why Aunt Emm is so natural towards Charley's brother's, but not Charley herself. I remember in my schooldays getting substitute teachers who only were used to teaching much younger pupils, or learning-support, and so were obviously out of their element when teaching and disciplining our class. It's a bit like that. Again, utterly fascinating, and I think is the real twist of the story (rather than the whole meaning behind I don't want Charley, you know that…

, which to be honest was predictable).

It would be too easy for me to make Aunt Emm a candidate for being a transman. That would simplify her predicament too much, but she is a butch and slightly moustached woman who is more attuned to the social and emotional profiles of boys, rather than Charley's more complicated feelings that weren't being addressed back at home. Aunt Emm in the end, is just a flawed person. The very end of the story avoids being trite and takes a unique turn; Charley and Aunt Emm's quietly agree not to like each other, and settle on cold peace. Just as Aunt Emm admitted she could never do with girls

, Charley decides she didn't want Aunt Emm either,

and that's okay. The story's ends on a sharp sentence that captures the strangely dreamy, peaceful atmosphere of the train carriage they share on the journey home: It was all right.

Published in 1972. It follows a girl named Jessie, who was sent to London nominally to receive private tuition and be boarded to attend a school; well out the picture of this story is her ill mother, who placed her there via a distant connection with a retired headmistress, Miss Mackie. This isn't a school dorm, however: the story begins with Jessie all alone in the drawing room of a row house: multi-storey and on an upmarket street, but ultimately a husk of Old Money, as most of the property is empty and unfurnished. Miss Mackie hardly finds time to actually tutor Jessie, who begins making these strange and plausibly deniable half-promises about boarding other children and making other tenancy arrangements.

As these sort-of promises go unrealised, Jessie begins to suspect Miss Mackie is a pathological liar. This is the basic source of conflict that drives the story, and it becomes almost something of a psychological thriller. Jessie is left suspended in a mood familiar with Robinson's works: people are unreliable, stupid, baffling. This is carried into a number of subplots: She slowly tries to understand a mysterious homeless woman who frequents The Square, and starts schools and finds it difficult to get along with a clique of girls whose motives she can't figure out.

Jessie's experience is so peculiarly specific and relatable to me. I'm reminded of my time turning up to job interviews and ending up not an interview, but being made to do some weird activity and forgotten about, being confused about what people want me to do and if they actually wanted me there. That's what this novel is about really, the feeling of being passively forgotten, becoming invisible. That bizarre, alienating feeling of no one telling you what's happening. This is if This is Robinson's most adult

novel, it seemed it was trying to aim higher than Marnie and Charley, with a tad more edgier language (bitch

) and slightly macabre imagery.

I need to get this out of the way: this is the most difficult to obtain Robinson novel. Its first print run as a hardback appears to be its last. No library holds a copy of it. I kept it on my eBay saved list for a year before a 50-year-old used copy showed up. What's going on? At least Robinson's other books are still somewhat available.

Published in 1977. This is a short story about a girl, Sarah, and her parents staying in a holiday home in rural Norfolk. Sarah is bored, which isn't helped by her mother's recently developed shyness of leaving the house, who's trying to recover from the trauma of a car accident. Eventually she comes across an elusive man, who appears to be homeless. She then unexpectedly finds a caravan park full of lively children. The story follows Sarah navigating a social life with these children, and getting to the bottom of her suspicions about them and the strange man.

This is a very odd book. The main character here, Sarah, does not seem to have any unique psychological profile, unlike all other protaganists Robinson has written. She and her family are quite normal, with really bland scenarios such as them all playing Ludo on a rainy day. The writing is very syntactically simple, I think even moreso than Mary-Mary, and to be honest I'm not a fan. It sort of felt like I was in primary school again, being made to read those rubbishy Biff and Chip learner-reader books.

However, the story is wildly unpredictable, and still features a few of the hallmarks of other Robinson's works. Firstly there's obviously the Norfolk setting, and briefly there's some enjoyable descriptions of its vast foreshores and what have you. Then there's the themes of vagrancy (enclosure politics) I mentioned: not just the apparently homeless guy, but also the caravan children as a whole. Are they holiday-makers, or travellers? If the latter, could that explain why the kids are kinda unruly? It's not clear. Just as Marnie romanticised gypsies with Anna in the role of the dumb beggar girl, and Charley conversely strips gypsies of that sort of romance, this story continues these ideas but with no particular position on either. Other recognisable things include anxiety over cruel parents, and the mandatory inclusion of the word beastly

somewhere.

Published in 1978. Meg and Maxie are siblings; Maxie is the younger brother, Meg is the older sister. They're left alone for a day—only a day—where together they're forced to reckon with the priorities of the French au pair girl nominally left to care for them, the perils of the seaside, and the mysterious woman who lives in the village. There's a lot going on in this story: the dynamic between Meg and Maxie that ranges from irritating to sweet, imagery that ranges from terrifying to dreamy, and circumstances that range from deadly to uplifting.

I really like this book. It's peak /comfy/. Where do I begin talking about this? I suppose I'll look at the high level details. This book is short; the paperback is pithy, petite, like it's pretending to be classic french literature. In fact it's so short that it's obvious the publisher struggled to print it to meet the minimum number of pages and signatures, because there's a distinct per-signature combing effect alongside the edge of the copy I own.

The general conflict of the story centers on the strained yet adorable relationship between Meg and Maxie. Maxie is kind of like Butters from South Park except maybe even more naive, with a dazed toddler-like grasp of reasoning and way of talking. He is probably about six years old. Meg thinks Maxie is cute but gets frustrated when it's not the time and place for him to be dim. The specific conflict is that Meg convinces Maxie that the mysterious woman who lives nearby is a witch, finding it favorable to arrest him in a state of innocent fear to keep him under control, which seems to go well at first but his uneasy conscience make things spiral out of control.

What follows is what might be called a series of sketches; there isn't much plot to this book and that's okay. The main achievement of this novel is its mood and style, mostly dreamy, sometimes terrifying, and at a certain point, rapturously uplifting. With that said, I don't have much to comment on it thematically. Only, it's just that there's just this one fascinating and well-written adult character whose moderately eccentric lifestyle is kind of inspiring. Makes me daydream about all the kinds of way I could model my living space (there are incredible descriptions of interior design in this novel) and ways I could spend all my days.

This is the only book where a character needs to do toilet. This had me wondering how Charley did it when she was out and about. Actually, how did Anna go to toilet spending so much time outside, cause my real life experience has found that coming back from the beach is no easy affair.